By Thomas Archer and Simal Rafique

Ingrid Pollard MBE is the 2022-2023 visiting Pilkington Professor for History of Art at the University of Manchester. Pollard is a British media artist, researcher and photographer whose work uses portraiture and traditional landscape imagery to explore social constructs such as nationhood, belonging and racial difference. Her work is included in the UK Arts Council Collection, Tate and the Victoria & Albert Museum. She graduated in 1988 from the London College of Printing, and in 1995 completed her MA in Photographic Studies at the University of Derby. In 2016 Pollard was awarded a PhD by the University of Westminster.

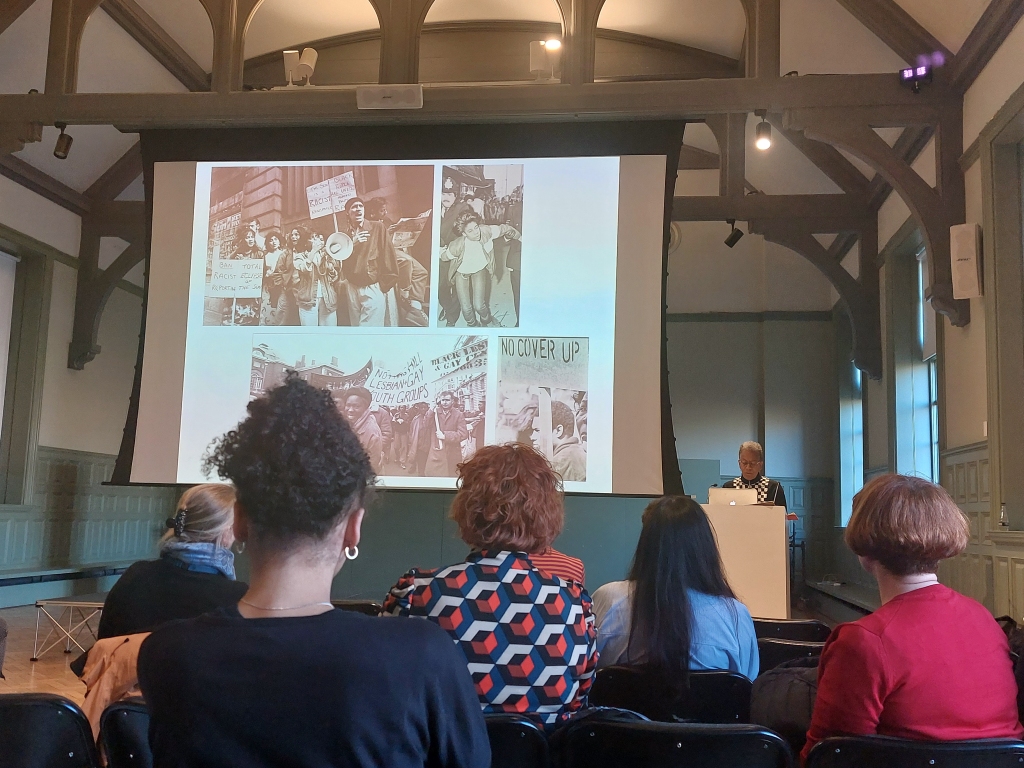

Pollard’s lecture at the Whitworth offered an insightful reflection on her Turner Prize nominated exhibition Carbon Slowly Turning, and was followed by an intimate discussion of select artworks spanning throughout Pollard’s career. The evening concluded with an enthusiastic Q&A session and drinks.

Ingrid Pollard’s lecture began with an examination of her postcard-based works collected in Seaside Series (1989), an exploration of the similarities between tourist memorabilia and the spoils of invasion throughout history. She showed photographs from her trips to Hastings. ‘My spoils’ she called them, ‘a bit like trophies, from my exploits’. Under a glass on one of the other boards is a quote from a passing traveller she encountered “…and what part of Africa do you come from?”. In some ways Pollard’s work is a criticism of the nature of tourism, encouraging us to think of why we follow these rituals of collecting souvenirs. She challenges us to think: what does this collection say about human experience through our cultures and biases?

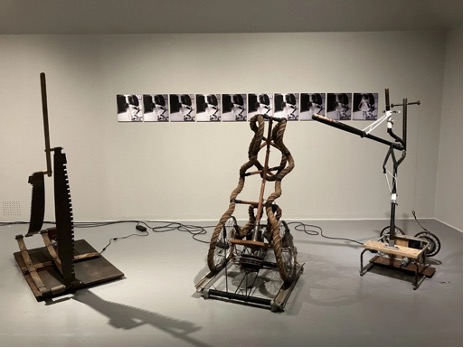

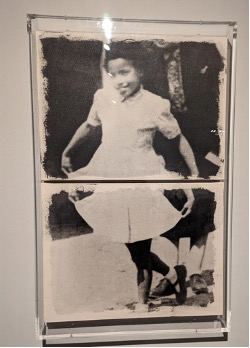

Carbon Slowly Turning features a sculptural work titled Bow Down and Very Low, created in 2021 in collaboration with kinetic artist Oliver Smart. Here one observes three ‘figures’ constructed out of industrially-manufactured materials like saws, ropes and wheels as well as a swinging baton. Midway through the lecture Pollard played a video of the machines in action: a mechanical arm with the baton groans ominously, quivering slightly as it turns the weapon from side to side. One sculpture, composed of two crossed saws, shakes violently as it builds tension and flings towards the camera, only to start the process again. The machines bow in their own way, unfamiliar to us. The uncanny nature of these ‘kinetic sculptures’ is confirmed by a photograph of repeated lenticular prints of a young black girl in a white dress, bowing and rising repetitively. The stills originate from a propaganda film titled Springtime in an English Village’, produced by the Colonial Film Unit. When talking about this series, Pollard remarked that the girl had been voted as the ‘May Queen’, but her actions could be interpreted as either a ‘subservient gesture or an acknowledgement and acceptance of regal power’. Pollard’s Bow Down and Very Low calls into question the history of colonialism, and the power relations that come with a shared legacy of inseparable threat and deference.

Ingrid Pollard was born in Georgetown, Guyana in 1953, and emigrated with her family to the United Kingdom at the age of four. As such questions of race and ethnicity inevitably emerge as an underlying consideration in the interpretation of Pollard’s oeuvre. However, it is imperative not to overstate this for, as the artist observes in an interview with the Guardian, “People want me to say that I’m alienated because then they can say: ‘Oh, I understand that. Black people should be in the Caribbean or Africa, that’s where they came from.’” Pollard’s landscape-based works have thus been interpreted as ‘a beacon for black engagement with Britain’s rural geography’, an act of defiance that rightfully claims a sense of nationhood and belonging for diasporic identities.

In The Valentine Days, Ingrid Pollard was commissioned by Autograph, the Association of Black Photographers, in 2017 to hand-tint a collection of modern prints made from nineteenth-century postcards of Jamaica. Using archives as a medium for imagining alternative realities, the images once served as travel souvenirs for European slave-owners in order to circulate and promote an image of their plantations as earthly paradises. According to Catherine Hall, ‘the British slave-owners who dominated plantation society in Jamaica wanted to establish a picture of the island as beautiful and prosperous, familiar and exotic, pastoral and tropical. They encouraged white settlement and countered negative accounts of slavery.’ One can certainly observe these aesthetic qualities in the luscious greenery of Pollard’s meticulous hand-tinting. Beyond this the relationship between the body and the landscape is a familiar motif in Pollard’s artistic practice, so viewers are encouraged to imagine what the lives of the enslaved people were really like at the plantation.

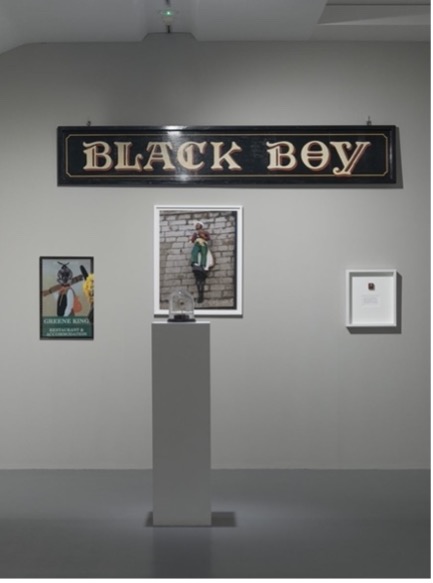

Seventeen of Sixty-Eight (2019) comprises of a series of photographs, pub signs, prints and paraphernalia created and collected over 25 years, demonstrating Pollard’s continuing engagement with archival research and the representation of the black figure in British popular culture. Here the title refers to the sixty-eight pubs in the UK that feature ‘Black Boy’ in their name. Seventeen of Sixty-Eight concerns itself with the Othering of the black figure in relation to environment, and how the legacy of colonialism persists in covert spaces. Visitors are encouraged to move around the gallery space to observe the details of the space, thus reflecting a concern with the racist politics of visibility.

Certainly Pollard’s lecture was a rare opportunity to hear an artist authentically discuss their work in their own terms. Her retrospective examination of Carbon Turning Slowly speaks to the relevance of even her earliest work from the nineteen-eighties. This impressive career has been widely celebrated, and while she was hesitant to speak about future plans in detail, it is clear there will be much more to come.